Interactions between atoms and light rule the behavior of our physical world, but, at the same time, can be extremely complex. Understanding and harnessing them is one of the major challenges for the development of quantum technologies.

To understand light-mediated interactions between atoms, it is common to isolate only two atomic levels, a ground level and an excited level, and view the atoms as tiny antennas with two poles that talk to each other. So, when an atom in a crystal lattice array is prepared in the excited state, it relaxes back to the ground state after some time by emitting a photon. The emitted photon does not necessarily escape out of the array, but instead, it can get absorbed by another ground-state atom, which then gets excited. Such an exchange of excitations also referred to as dipole-dipole interaction, is key for making atoms interact, even when they cannot bump into each other.

“While the underlying idea is very simple, as many photons are exchanged between many atoms, the state of the system can become correlated, or highly entangled, quickly,” explains JILA and NIST Fellow and University of Colorado Boulder physics professor Ana Maria Rey. “I cannot think of a single atom as an independent object. Instead, I need to keep track of how its state depends on the state of many other atoms in the array. This is intractable with current computational methods. In the absence of an external drive, the generated entanglement typically disappears since all atoms relax to the ground state.”

Atoms can, however, have more than two atomic levels. Interactions in the system can change drastically if more than two internal levels are allowed to participate in the dynamics. In a two-level system (weak excitation) with only one photon and, at most, one excited atom in the array, one just needs to track the single excited atom. While this is numerically tractable, it is not so helpful for quantum technologies since the atoms could be thought of more as classical antennas.

In contrast, by allowing just one additional ground level per atom, even with a single excitation, the number of configurations accessible to the system grows exponentially, drastically increasing the complexity. Understanding atom-light interaction in multi-level settings is an extremely difficult problem, and up to now it has eluded both theorists and experimentalists.

Rey explains, “However, it can be extremely useful, not only because it can generate highly entangled states which can be preserved in the absence of a drive since atoms in the ground levels do not decay.’’

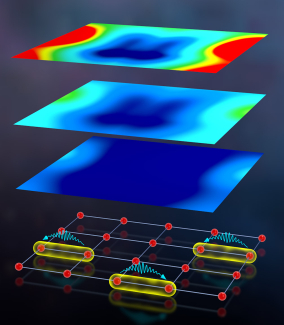

Now, in a recent study published in Physical Review Letters, Rey and JILA and NIST Fellow James K. Thompson, along with graduate student Sanaa Agarwal and researcher Asier Piñeiro Orioli from the University of Strasbourg, studied atom-light interactions in the case of effective four-level atoms, two ground (or metastable) and two excited levels arranged in specific one-dimensional and two-dimensional crystal lattices.

“We know that including the full multilevel structure of atoms can give us richer physics and new phenomena, which are promising for entangled state generation,” says Agarwal, the paper’s first author. With quantum technologies like computing and secure communications requiring entanglement, understanding how to create stable, interconnected atomic systems has become a priority.

From Two to Four Internal States

For this study, the researchers focused on isolating four energy levels in strontium atoms, arranged in either one-dimensional (1D) or two-dimensional (2D) configurations where the atoms are loaded in a special configuration in which they are closer to each other than the wavelength of the laser light used to excite them.

The study concentrated on a set of internal levels with a much smaller energy separation than typical optical transitions. Instead of using truly ground-state levels, they proposed using metastable levels where atoms can live for a very long time.

This very interesting set of levels has not been explored much before since it requires a special laser with a very long wavelength, but Thompson plans to have this laser in his lab.

“We plan to build the necessary capabilities in our lab to first knock the atom into an excited state that lives for a really long time,” Thompson says. “This will let us use a 2.9-micron wavelength transition between this so-called metastable-state excited-state 3P2 in strontium and another excited-state 3D3 state. This wavelength is about eight times longer than the usual separation between nearby atoms trapped in an optical lattice in our lab. By having a transition wavelength much longer than the trapping light wavelength, we will be able to realize strong and programmable interactions via this photon exchange that happens when the atoms are jammed in close to each other.”

Agarwal adds, “The atoms need to be very close, as interactions weaken with distance, eventually becoming lost due to other sources of decoherence [noise]. Keeping atoms close allows interactions to dominate, preserving the growth of entanglement.”

The team focused on the weak and far-from-resonance regime where atoms are allowed to virtually “trade” photons, i.e., moving them between ground states without permanently occupying an excited state.

“By exchanging photons, atoms are effectively only moving between different configurations in the ground state levels, which simplifies our calculations by reducing the number of states accessible to the system,” Agarwal adds. “It’s easier to eliminate the excited states and focus on the metastable state dynamics, where we observe growing correlations, which furthermore can be preserved when the laser is turned off.

Creating A Spin Model for Entanglement

In the regime where the excited levels are only “virtually” populated, and only atoms can occupy the metastable state levels, the four-level problem can be reduced back to a two-level system at the cost of dealing with much more complex interactions, which involves not only pair-wise interactions but multi-atom interaction.

Rey explains, “We focused in the far from a resonant regime where to leading order, only two atoms interact at a given time. In this case, the Hamiltonian describing the metastable state dynamics maps back to a well-characterized spin model.”

The team used this well-known model to study what are called “spin waves”—coordinated low-energy excitations of atomic spins—across the lattice arrangement. Moreover, by controlling the polarization and propagation direction of the photons of the laser exciting the atoms, the researchers could determine which “spin-wave pattern” became dominantly entangled. The entanglement observed was spin-squeezing, a specific form of entanglement that has increased sensitivity to external noise and thus useful for metrology.

“The spin squeezing in our system can be experimentally measured and serves as a witness of quantum entanglement. Our setup also has possible applications in simulating many-body physics,” Agarwal says.

This finding is especially significant, as it implies that quantum systems could maintain entanglement over long periods, without needing constant intervention to prevent decoherence.

Limitations in Simulations

While the team’s model offered promising insights, it also faced limitations in accurately simulating the system over time. One of the key limitations arose from the dipole-dipole interactions, which, unlike simpler interactions, involve long-range forces that couple atoms both near and far in the lattice. Furthermore, these couplings are anisotropic and depend on the relative orientation of the atomic dipoles, making the system more complex. Each atom interacts differently with its neighbors spaced along different directions in the lattice, leading to varying interaction strengths and signs across the array.

Other popular simulation techniques designed for short-range interactions fail when applied to long-range interactions, as they aren’t equipped to handle the many correlations that develop over time. Although some other methods are more appropriate for long-range atomic interactions, they are constrained to small atom numbers due to their computational complexity, limiting the researchers’ ability to observe the long-time progression of correlations in a large system.

Diving Further into Internal States

The team’s findings could open new avenues in quantum information science and quantum computing, offering a potential path for the development of highly entangled and scalable quantum systems.

“We’re inching closer to systems that could sustain entanglement reliably, which is a crucial step for future quantum applications,” says Agarwal.

Looking forward, the research team plans to explore how more extensive multilevel systems might enhance entanglement potential.

“In atoms like strontium, with as many as 10 ground and excited levels each, the complexity grows significantly, and we want to see how this impacts entanglement,” Agarwal says. “Furthermore, while we have focused here on interactions between atoms in free space, one excited extension is to understand how these interactions can interplay with additional photon-mediated interactions [that are] built when atoms are instead placed inside an optical cavity or in nanophotonic devices,” she adds

“The competition between the infinite range interactions mediated by the cavity photons and the dipole-dipole interactions described here can open fantastic opportunities to harness light-mediated quantum gates, entanglement distribution, and programmable quantum many-body physics,” says Thompson.

This work was supported by the Vannevar Bush Faculty Fellowship (VBFF), the National Science Foundation (NSF), the Joint Institute for Laboratory Astrophysics-Physics Frontier Center (JILA-PFC), the Quantum Systems Accelerator (QSA), and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)

Written by Kenna Hughes-Castleberry, JILA Science Communicator

The Physics Frontiers Centers (PFC) program supports university-based centers and institutes where the collective efforts of a larger group of individuals can enable transformational advances in the most promising research areas. The program is designed to foster major breakthroughs at the intellectual frontiers of physics by providing needed resources such as combinations of talents, skills, disciplines, and/or specialized infrastructure, not usually available to individual investigators or small groups, in an environment in which the collective efforts of the larger group can be shown to be seminal to promoting significant progress in the science and the education of students. PFCs also include creative, substantive activities aimed at enhancing education, broadening participation of traditionally underrepresented groups, and outreach to the scientific community and general public.

The Physics Frontiers Centers (PFC) program supports university-based centers and institutes where the collective efforts of a larger group of individuals can enable transformational advances in the most promising research areas. The program is designed to foster major breakthroughs at the intellectual frontiers of physics by providing needed resources such as combinations of talents, skills, disciplines, and/or specialized infrastructure, not usually available to individual investigators or small groups, in an environment in which the collective efforts of the larger group can be shown to be seminal to promoting significant progress in the science and the education of students. PFCs also include creative, substantive activities aimed at enhancing education, broadening participation of traditionally underrepresented groups, and outreach to the scientific community and general public.